Table of contents of the article

ToggleStem rot is a disease that affects the strength of the plant and leads to poor yield. In this article from the “WORLD OF PLANTS” website, we review the symptoms of infection and methods of prevention and control.

Cause of stem rot disease

Stem rot - Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, scientific name.

Type of disease: fungal

Sclerotinia stem rot is caused by the soil-borne fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, which can survive for long periods of time on plant debris or in the soil. Most of its life cycle is in the soil, which explains why symptoms begin in leaves and plant parts close to the ground. When conditions are favourable, it resumes growth on organic matter, sometimes by invading plant tissue. As it colonizes all parts of the plant, seeds may also carry the pathogen, either on the seed coat or internally. The new batch of spores produced on the plant is airborne. The humid climate under the foliage favors the germs to spread on the stems. Initial growth of the fungus requires several hours of humid air and temperatures between 15 and 24 degrees Celsius. Its growth is also compatible with the presence of external nutrients. This mushroom has a wide range of families such as beans, cabbage, carrots and canola.

Host of stem rot disease

. It is also found in beans, pepper, hot pepper, eggplant, peas, cucumber, zucchini, tomatoes, cabbage, potatoes, peas, chickpeas, cotton, soybeans, onions, okra, watermelon, canola, kerala lentils (bitter cucumber), and tobacco.

Suitable conditions for stem rot disease

The humid climate under the foliage favors the germs to spread on the stems. Initial growth of the fungus requires several hours of humid air and temperatures between 15 and 24 degrees Celsius. Its growth is also compatible with the presence of external nutrients.

Stem rot disease cycle

The resulting sclerotia on diseased tissue are winter-surviving structures, about 2 to 20 mm long. Sclerotia lives dormant on or in the soil during the winter months. In the spring, summer, and fall months, under humid conditions, scleroderma develops into small, tan-colored, trumpet-shaped, mushroom-like structures called apothecia. The spores produced in the myrrh are called ascospores, which are forcibly discharged and carried by the wind to susceptible plants. Apothecia are frequently found in moist, sheltered places beneath the lower leaves of mature plants.

Ascospores require nutrients and a thin layer of water on the plant's surface to be able to germinate and infect the plant. The flowers of many plants, including weeds, are an excellent source of nutrients for ascospore germination. The most frequently observed nutrient sources in New York produce fields are velvet leaves and common ragweed flowers, which are often found infested with Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Bean flowers are important in these crops. The pathogen grows from infected flower parts into healthy stems and pods when they are in contact with each other.

Cool, moist conditions (below 85 degrees F) favor white mold development, but the fungus can grow over a wide range of temperatures. The fungus requires significant moisture for sclerotia to germinate and for ascospores to infect plants. It has been observed that white mold is more prevalent in bean and cabbage crops where there is restricted air circulation due to low-lying and forested areas surrounding the field. This is because poor air drainage allows moisture to be retained in the soil and plants for a longer period of time. The resulting extended wet period favors the development of white mold.

Effect of stem rot disease

Short rotations, rotations with other sensitive crops, or frequent use of sensitive varieties.

Poor management of sensitive broadleaf weeds.

Fields that have poorly drained air pockets, tree lines, or other natural barriers that reduce air movement.

Symptoms of stem rot disease

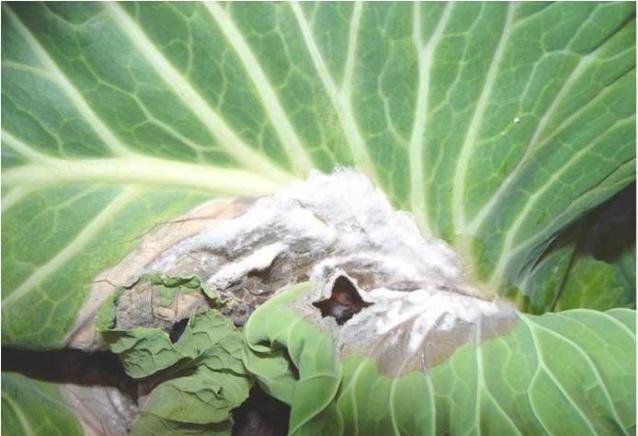

- Spots appear on the fruits, leaves or petioles.

- The spots are covered with a cottony white mold.

- Later, wart-like structures form.

- Wilting of the stem and upper parts of the plant occurs.

- Symptoms vary between host species, but there are a number of similarities. Initially, irregular, water-soaked spots appear on the fruits, leaves or petioles. As they expand, the affected areas become covered with a white, cottony, fungal layer, and in later stages are scattered with visible gray or black sclerotia-like reproductive structures called sclerotia.

Preventive measures for stem rot disease

- Use healthy seeds from certified sources.

- Choose resistant or more tolerant varieties of the crop in question if available.

- Do not plant in previously infected land.

- Plant at wide planting distances to allow good ventilation of crops.

- Use wire or wooden supports to secure the plants.

- Monitor the field for symptoms of the disease.

- Control weeds in the field and surrounding areas.

- Pruning branches or affected parts of crops.

- Do not over-fertilize during the late growth stages.

- Avoid heavy irrigation during the late growth stages.

- Do not plow the land, as not plowing reduces the chances of infection and disease development.

- Rotate crops with other non-host crops, such as grains.

Organic control of stem rot disease

Granular formulations of spores of the parasitic fungus Coniothyrium minitans or Trichoderma species have been applied to soil to reduce the fungal load of Sclerotinia, thereby inhibiting the development of the disease.

Chemical control of stem rot

Always take an integrated approach with preventive measures together with biological resistance, if available. Foliar fungicides are recommended for use only in fields with severe disease development. Treatment methods vary depending on the crop concerned and its growth stage. Controlling sclerotinia on cabbage, tomatoes and beans is very difficult. However, fungicides based on iprodione and copper oxychloride at 3 g/L of water have shown effective control on lettuce and peanuts. The development of resistance to some of these compounds has been observed.

In conclusion, we would like to note that we, at the world of plants website, offer you all the necessary services in the world of plants, we provide all farmers and those interested in plants with three main services::-

- Artificial intelligence consulting service to help you identify diseases that affect plants and how to deal with them.

- Blog about plants, plant diseases and care of various crops ... You are currently browsing one of her articles right now.

- An application that provides agricultural consultations to clients, as well as a service for imaging diseases and knowing their treatment for free – Click to download the Android version from Google Play Store، Click to download the IOS version from the Apple App Store.

References

- Margaret Tuttle McGrath

- Associate Professor

- Long Island Horticultural Research and Extension Center (LIHREC)

- Department of Plant Pathology and Plant Microbiology

- College of Integrative Plant Sciences

- College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

- Cornell University Mtm3@cornell.edu

- Originally prepared for the VegetalMD Online website as a Fact Sheet on White Mold on Beans by Helen R. Dillard and on Cabbage by George S. Abaway and J.E. Hunter. Edited and updated in August 2022 by Margaret Tuttle McGrath and Sarah Pethybridge.

- Scout White Mold, Crop Protection Net CPN-1010B, 2015

- Soybean Stem Disease Scouting, Crop Protection Network CPN 1002, 2015

- Detection of white mold in soybean triple version, Crop Protection Net CPN-1002A, 2015

- Soybean White Rot (Sclerotinia Stem Rot) video, Plant Management Network, 2016

- Sporecaster, soybean white mold predictor (smartphone app), University of Wisconsin

- Information about this disease provided by Douglas J. Jardine, Professor Emeritus, Kansas State University and Crop Protection Network 4/2020